2024 Cicada Emergence FAQ

go.ncsu.edu/readext?987180

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

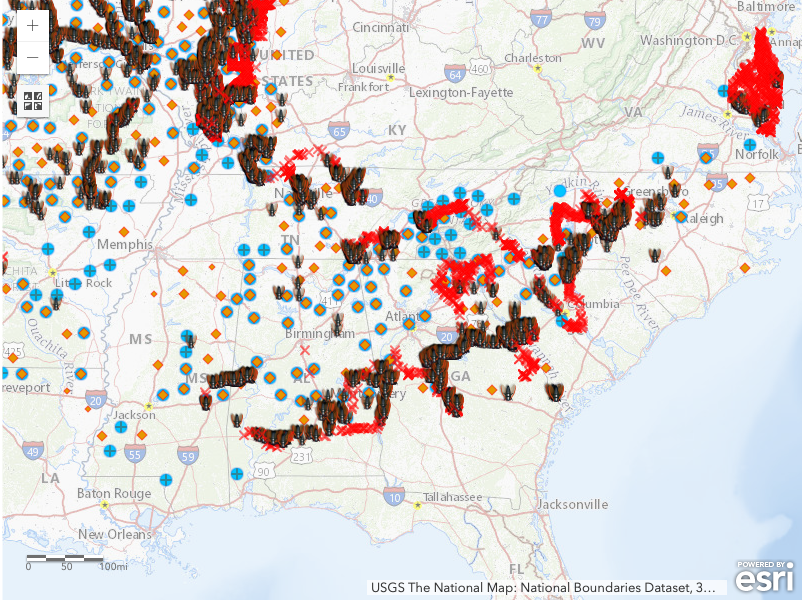

Collapse ▲The emergence of the periodical cicadas is creeping closer! This phenomenon will occur across the Eastern United States and contains two main broods: a 13-year brood which is also known by its overall brood number 19 (XIX) and the 17-year brood which is also known by its brood number 13 (XIII). This year, both the 13-year emerging brood (XIX) and the 17-year emerging brood (XIII) will emerge at the same time. The last time both of these broods emerged at the same time was 221 years ago! So how will this event impact us, and should we be concerned? Spoiler alert, there is no need to panic. Here are some answers to commonly asked questions, along with some additional information about cicadas and how the cicada emergence will impact us this year.

Frequently asked questions:

Is this a year where there will be lots of cicadas?

Yes, potentially depending on where you live! This year is an emergence year for the 17-year (XIII) brood and the 13-year (XIX) brood. We expect this year to see an increase in cicada number in many areas of the country and potentially in our area.

13-year Brood

The 13-year brood, as the name suggests, emerges every 13 years and more directly impacts the southeastern United States. This area includes Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Missouri, and Tennessee. Other states like Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, and South Carolina should have strong emergences in certain areas, and states like Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Virginia will have very limited emergences. In particular, the 13 year brood (XIX) has historically been present in Buncombe County, as well as other areas of central/eastern North Carolina. This is the cicada brood that will emerge and impact some in our area.

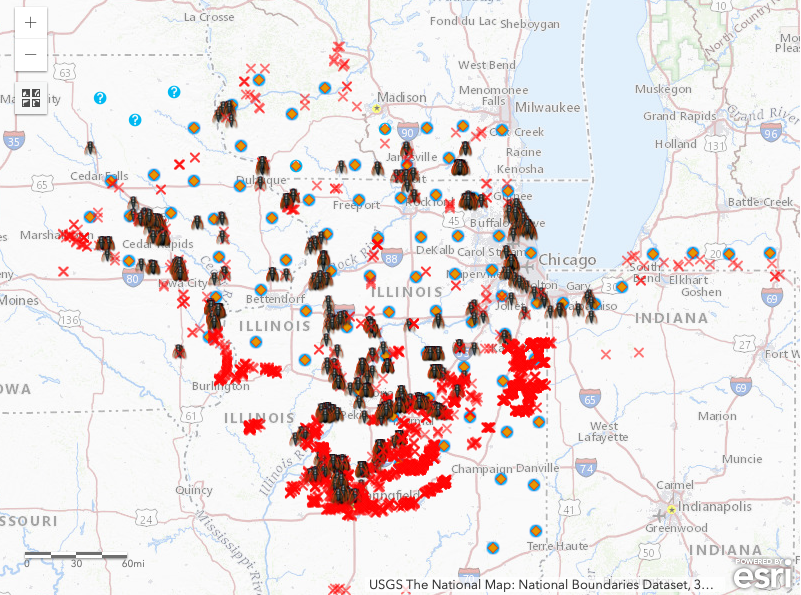

17-year Brood

The 17-year brood emerges and impacts Michigan and Illinois, therefore the impact of the 17-year brood is nonexistent in the southeastern United States. The only area in the country where there will be potential crossover of both the 17-year brood and the 13-year brood at the same time is in southern Illinois where populations have the potential to be heavier. Due to the fact that this brood will not impact our area, I will only be talking about the 13-year brood from now on.

When was the last time large populations of cicadas emerged in Western North Carolina?

The last time a large brood (brood 6; VI) emerged in our area was in 2017. You may be asking yourself, well why do I see (or more likely hear) cicadas every year then? Good question! There are periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.) which follow the emergence patterns of their brood (in the case of this year 13 years between emerging events for brood XIX), and then there are the annual or dogday cicadas (Diceroprocta sp. and Okanagana sp.) that emerge typically every year in much smaller numbers. The different species of cicada that emerge have different calls and different life cycles. This year is unique due to the fact that cicadas that you see every year (annual cicada), will emerge with the 13-year brood (XIX) at the same time in some areas of western NC. Other broods that have impacted our area in the past include the before mentioned brood VI and brood XIV.

What time of year do cicadas normally emerge? What is their general life cycle?

So it depends on the species of cicada we are talking about. When discussing the periodical cicada, we know that it takes approximately 13 years for the 13-year brood (XIX) to fully complete its lifecycle. The adults emerge and lay eggs in the bark of trees and shrubs as adults (usually the process from emergence to laying of eggs takes one to two weeks).

Once they emerge, they can fly up to a couple hundred meters, meaning that there will be isolated pockets that are heavier than others. Once their eggs are laid, nymphs hatch in 6-10 weeks, and drop to the ground where they stay feeding on tree roots for approximately 13 years. The nymphs go through 5 different growth stages as they increase in size and will eventually emerge to molt as adults in the final 13th year of their life cycle. Emergence in the final year is triggered once the average temperature of the ground reaches 64°F at approximately 8” below the ground surface. In our area, emergence is typically seen early to mid May. The annual or dogday cicada species typically emerges in June in much smaller numbers, again with the ground temperature being the biggest factor in timing of their emergence as well.

Should I be concerned about damage to my plants in the landscape, and if so, what strategies can I implement to deal with cicadas?

Most people should not be concerned about cicada’s damaging their plants. Older, established plants will show minimal damage with some flagging of the terminal branches possible (see below). This occurs when cicadas feed on woody stem tissue and or deposit their eggs into the bark of trees. Generally the tree and shrub can recover fairly quickly, with no long-term damage seen. Younger trees that have just been planted might see more damage due to not being fully established and not having a well-developed canopy. In general, it is recommended to both orchard and nursery owners to refrain from planting large numbers of trees, if possible, prior to the periodical cicada emergence. Chemical treatment through pesticides is generally not recommended and not effective due to the sheer number of periodical cicadas that emerge, while kaolin clay (Surround) saw some effectiveness in slowing egg laying damage (see prior study). If there is a high value tree in a home landscape, the best form of management is exclusion through bird netting over valuable specimens to prevent feeding and laying of eggs, and therefore preventing dieback of scaffolding branches.

Picture of flagging and necrosis of terminal branches of trees infested with periodical cicadas. Source: Eric R. Day

Should I be concerned about cicadas harming my pets or biting me?

Cicadas cause no harm to humans, and pets. Contrary to some anecdotal stories, they do not bite or sting. They are actually a great food source for birds, and other animals that eat insects which means that ecologically the emergence this year will provide additional food resources to many different organisms.

For more information about periodical and annual cicadas, the upcoming emergence, and other helpful information please visit the links below and/or contact your local Cooperative Extension office.

UCONN Periodical Cicada Information Pages

The Cicadas Are Coming, Fear Not Though- NC Extension